Louisa Chaton

Textile Transfers – The Collections of Rosalia Rothansl and Mileva Stoisavljevic-Roller

Louisa Chaton

Textile Transfers – The Collections of Rosalia Rothansl and Mileva Stoisavljevic-Roller

Fashion, folk, and femininity – how these concepts intersect and are constructed through art collections is the central theme of the exhibition Textile Transfers, curated by Stefanie Kitzberger and Eva Klimpel. At its core are two significant yet overlooked figures of the Viennese arts and crafts movement: Rosalia Rothansl (1870–1945) and Mileva Stoisavljevic-Roller (1886–1949). Anyone expecting a brief stroll through the baroque venue and a modest display of textile pieces from the Collection and Archive of Die Angewandte (University of Applied Arts Vienna) is in for a surprise.

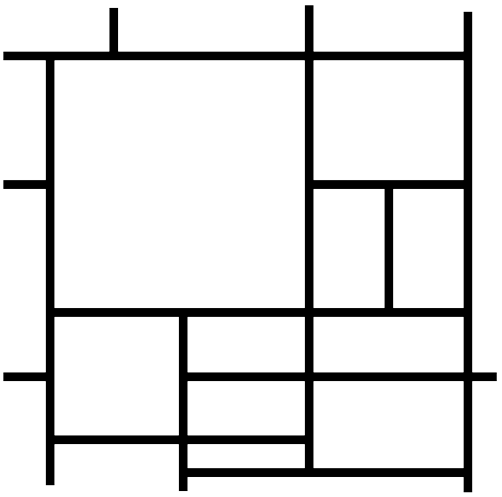

1. Exhibition view of Textile Transfers – Die Sammlungen von Rosalia Rothansl und Mileva Stoisavljevic-Roller, Universität für Angewandte Kunst Wien. Photo – Manuel Lopez Carreon

Textile Transfers offers much more than an aesthetic experience or a historical detour. Through its exhibits and accompanying documentation, the project explores the context of the Viennese arts and crafts reform with a specific focus on the infatuation with so-called ‘domestic industry’ which emerged in the second half of the nineteenth century and continued to be widespread in the interwar period. This interdisciplinary interest, described as primitivist in art history, relied on a cultural-political, artistic, and scholarly discourse praising the non-alienated, domestic mode of working in rural regions of the Habsburg Empire, rooted in agriculture and ‘untouched’ by the process of industrialisation. Artists, intellectuals, and other private individuals, including women like Rothansl and Stoisavljevic, but also institutions collected so-called ‘Volkskunst’ (folk art). These works served both as formal and ornamental inspiration for transcending historicism, a trend that draws its sources and inspiration from styles from the past. This reform of the arts contributed to nationalist discourse by mythologising a ‘new’ multi-ethnic identity in the Dual Monarchy and therefore helping to forge a common identity based on belonging to the empire. The exhibition Textile Transfers examines these topics with particular attention to colonial dimensions as well as gender and class-related issues.

In five different rooms, the curators present over 160 artifacts – including clothes, needlework, photographs, prints, drawings, and archival files and books from Die Angewandte’s collection as well as other Viennese institutions including the Museum of Applied Arts (MAK) and the Leopold Museum – all described and analysed in two leaflets that synthesise three years of research. Textile Transfers is the first outcome of a research project led by Klimpel and Kitzenberger since 2022 at the Department of Museum Studies at the University. In this sense, it represents just the beginning of a broader undertaking involving both professors and students, with an essay and a more extensive publication forthcoming. The exhibition was also accompanied by a series of three lectures by the Centre for Modern Art & Theory of Brno held in Vienna at Die Angewandte during May and June. This programme emphasised the stimulating role of this project for research about Central Europe, particularly through gender studies and postcolonial perspectives.

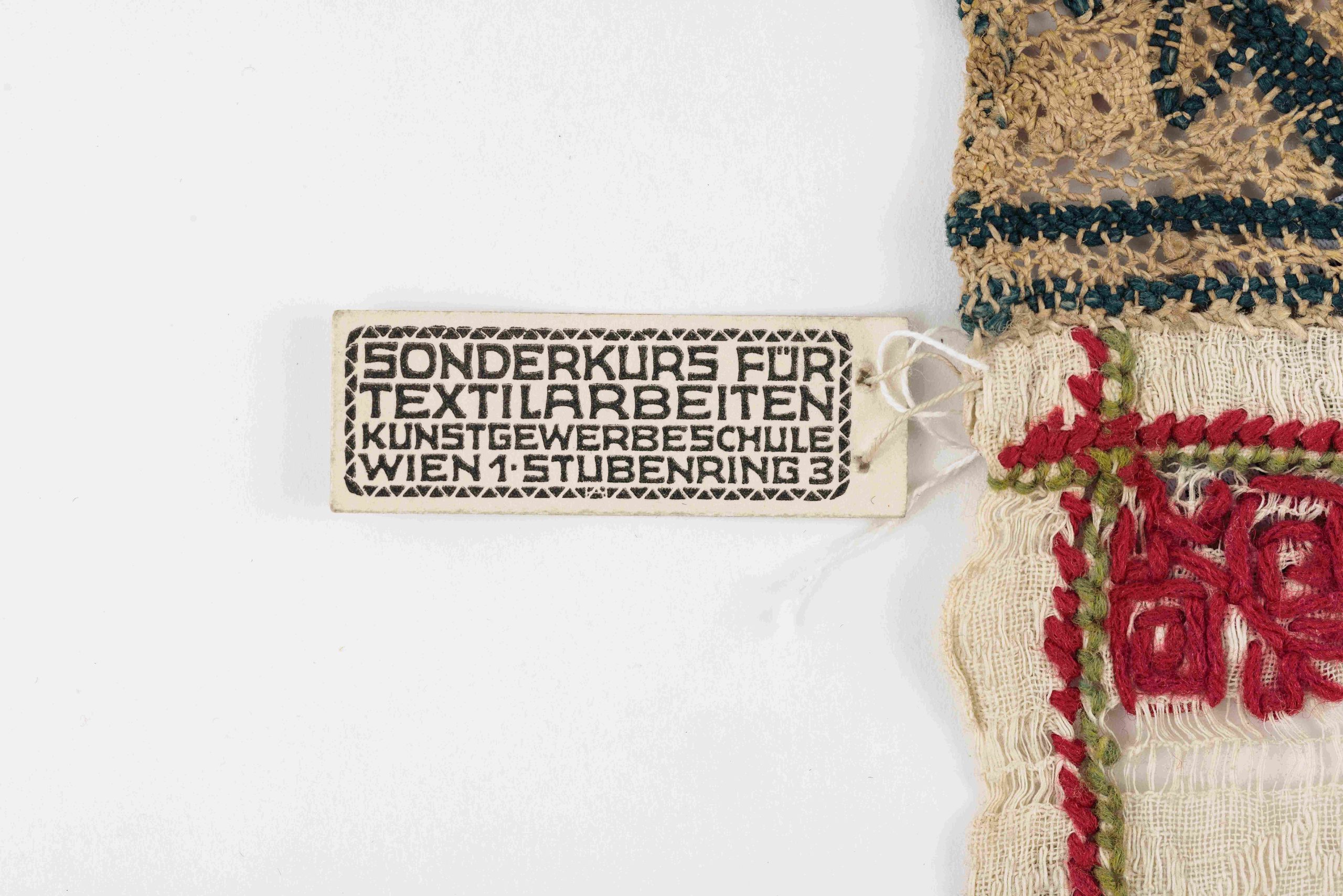

The aim of the exhibition is to contextualise the textile collections of Rothansl and Stoisavljevic, who are described as ‘examples of both the professionalisation of women artists in the context of admission of women to what was then called the Vienna School of Arts and Crafts, as well as of the modernist orientation of its artistic pedagogy in the early 20th century. Indeed, Rothansl, who is primarily known for being one of the first women in Central Europe to receive a professorship, assembled the displayed pieces as a ‘Lehrmittelsammlung’ (collection of teaching materials). Most items of her collection initially came from rural regions of Central and Eastern Europe such as Galicia, Slavonia or Transylvania, which were the peripheries of the Habsburg Empire, and were brought to its capital, Vienna. This transfer from periphery to centre implies a colonial entanglement, which is reinforced through the decontextualization of the textiles and their reduction to ahistorical sources of inspiration. In the exhibition, the costumes are presented on custom-made mannequins crafted to be nearly invisible by the conservator Klimpel, who, in doing so, reconstructs and questions the role of these textiles in teaching practices as formal and technical models.

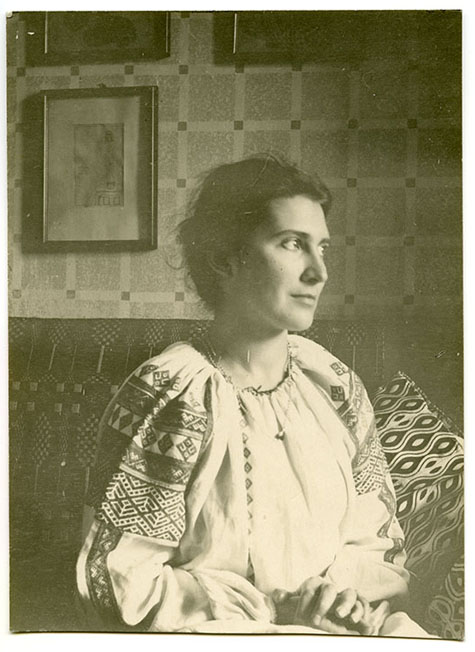

5. Unknown, Portrait of Mileva Stoisavljevic-Roller (?), Silver gelatine print on baryta paper; 12 x 8,8 cm

Unlike Rothansl, Stoisavljevic used her collection as a performative means of self-expression, which bears a similar colonial dimension as she hence negated the objects’ history to focus solely on their form. Among others, photographs of Emilie Flöge show how widespread this practice was in the Viennese Secessionist circles in which she moved. In the leaflet, the curators highlight the unclear provenance of the worn garments, some of which are on display. Partly sourced from South and East Asia, they may have been obtained or stolen as part of an asymmetrical power relationship via the colonial regime in the Austrian concession area established in 1901 in Tientsin. Hence, Textile Transfers emphasises that the term ‘Volkskunst’, instead of circumscribing a precise set of objects, mostly amalgamates works with origins as different as the ‘peripheries’ of Austria-Hungary and fantasised ‘Orient’, a term that encompasses the whole of the Asian continent as well as parts of the Maghreb.

These dynamics in “The Discovery of “Domestic Industry” or “Folk Art” and the Arts and Crafts Reform” are themes in the first two rooms as indicated in the comprehensive documentation. Kitzenberger and Klimpel explain how these categories reflect a colonial gaze, as well as classist and sexist prejudices that structured the hierarchy of artistic genres and techniques. Indeed, the ‘Volkskunst’, mostly done by women and/or people from the peasant or artisan class, did not achieve the status of autonomous artwork, remaining either a source of inspiration or of knowledge about societies supposedly unevolved and untouched by modern civilisation. Through various objects, student works, photographs, archives, and books, the curators link theoretical frameworks in newly established humanities disciplines to contemporary museum and collection practices. Therefore, they demonstrate how this primitivist understanding of culture and art contributed to broader nationalist and imperial dynamics, as well as how it shaped the theories of major art historians, such as Rudolf Eitelberger or Alois Riegl.

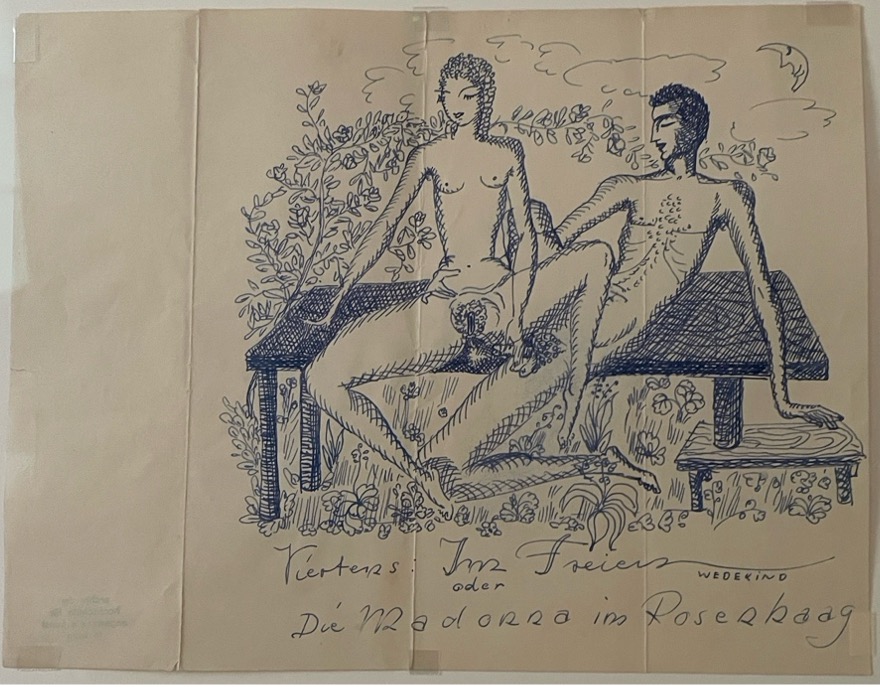

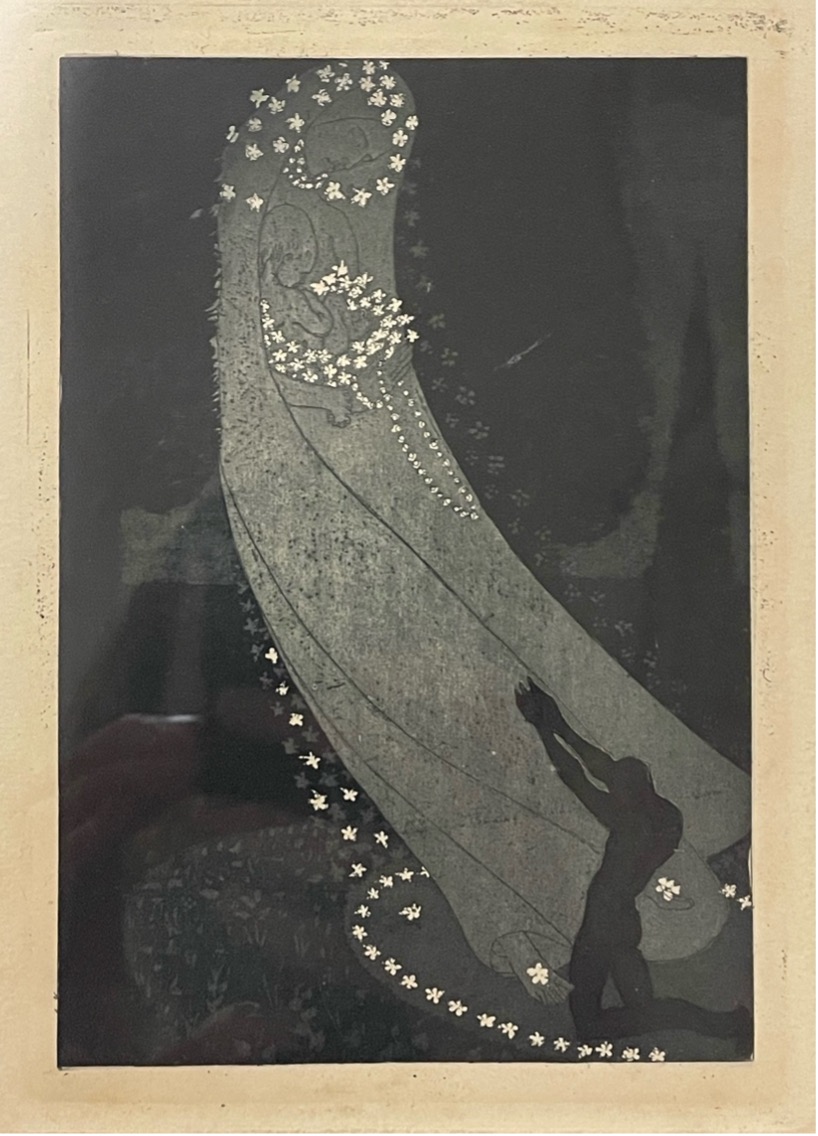

Textile Transfers seeks to distinguish a Primitivism peculiar to Viennese Modernism around 1900 by showing how artists of the decorative arts reform relied on the appropriation of artistic knowledge and practices of supposedly anti-modern or primitive items to develop their modernist conceptions. While photographs on wooden tables and clothes displayed in the second room highlight the influence of ‘Japonisme’ in Secessionist circles, Rooms 3, 5, and 6 are dedicated to “Rosalia Rothansl as Designer and Teacher”. Several works of her students, whose biographies can be found in the guide, showcase the spread of the primitivist aesthetic into the interwar period. The curators, therefore, address the intricate question of how the anti-modern has become modern by shedding light on ‘Kunstgewerblerinnen’ (craftswomen), many of whom were only ‘rediscovered’ in 2021 at the MAK with the Frauen der Wiener Werkstätte exhibition. Camilla Birke-Eber (1905-1988), Maria Likarz-Strauss (1893-1971), Felice Rix-Ueno (1893-1967) or Emmy Zweybrück-Prochaska (1890-1956) are only a few of the biographies mentioned in the leaflet. Between the beautiful fashion drawings, the stunning garments made from printed fabrics, and the exquisite pendants, it’s almost hard to focus on any one specific item. But if there was one work that would hold both attention and memories, it would, paradoxically, be the playful pornographic drawings by artist Vally Wieselthier.

The rehabilitation of women, too long confined by historiography to the status of technical workers or muses – i.e., recognising their agency – also implies considering their responsibility in cultural and political mutations brought about by the reform movement. As it can only be understood thanks to the guide, this critical assessment of their artistic heritage is the topic of the smaller and darker Room 4, where Stoisavljevic’s work stands in focus. The curators underline the role of the Viennese Reform Dress movement, defined as “manifestation of the struggle for gender equality at the turn of the century, which was linked to both the Lebensreform [life reform] movement and the idea of the Gesamtkunstwerk [total work of art], which itself emerged from the arts and crafts movement.” However, Stoisavljevic’s graphic designs, published in Ver Sacrum or Die Fläche, widely overlooked until this exhibition, as well as photographs of her and Emilie Flöge, paradoxically showcase a conservative or even reactionary image of women. For instance, the curators highlight her cult of maternity, as well as her involvement in German nationalism through her body image and the echoes of Wagnerian myths in her works. The leaflet’s concluding text clarifies: there are explicit links between National Socialism and actors of the Klimt Gruppe (Klimt group) formed by the artists who resigned from the Viennese Secession in 1905, such as Josef Hoffmann but also members of Stoisavljevic’s family. Thus, these artists contributed to a growing climate of anti-Semitism in Vienna, which puts the narrative of the movement’s supposedly ‘progressive’ character into perspective.

Textile Transfers not only contributes to a renewed understanding of the period and concepts such as ‘Volkskunst’ but also manages a self-critical and self-analytical assessment of the university’s collections and their history. The curators provide a nuanced reassessment of Rothansl and Stoisavljevic’s contributions to Viennese Modernism, without euphemising the colonial and racial dynamics in this process, or idealising supposedly exceptional figures, as is sometimes the case in feminist art history.

Nevertheless, the exhibition requires time and concentration. It is directed at an informed audience eager to deepen their knowledge of artists from Vienna’s School of Applied Arts and broaden their understanding of Viennese Modernism, rather than at casual visitors seeking blissful, silent contemplation. Indeed, although many displayed works deserve consideration, it is almost as if the conclusion of the research attracts the most attention, such is the density of information and the precision of the analyses presented in the documentation, leaving one eager to delve deeper with forthcoming publications. In the meantime, there is still until the 15th of July to visit the exhibition at Die Angewandte’s University Gallery Heiligenkreuzerhof.

10. Unknown Artist, Rosalia Rothansl School, Embroidery fragments (Bukovina), teaching aid (?); Linen, embroidered silk, crochet; 14,5 x 21,5 x 0,2 cm

- Stefanie Kitzberger / Eva Klimpel, “Volkskunst” und Kunstgewerbe. Einleitendes zu den Textilsammlungen von Rosalia Rothansl und Mileva Stoisavljevic-Roller, in: Stefanie Kitzberger / Eva Klimpel (eds.), Sammeln, Aneignen, Übersetzen. Rosalia Rothansl, Mileva Stoisavljevic-Roller und die moderne Hausindustrie, New Tony Press, Berlin 2025, pp. 11-16.

- The seminar was entitled “Moderne Hausindustrie‘ und kulturelle Übersetzung”, see: Ibid, pp. 15-16.

- More about the entanglement about modernist artistic pedagogy and primitivism, see: Megan Brandow-Faller, Playing with design – Playfulness and Whimsy in the Feminist Design Networks of Fanny Harlfinger-Zakucka, in: Elana Shapira/ Ann-Kathrin Rossberg (eds.), Gestalterinnen: Frauen, Design und Gesellschaft im Wien der Zwischenkriegszeit, De Gruyter, 2023, pp. 75.

- The colonial dimension of dichotomies such as centre/peripheries, have been explored by the postcolonial theorist Stuart Hall: Stuart Hall/ David Morley, The West and the Rest: Discourse and Power [1992], in: dies. Essential Essays, Volume 2, New York 2018, S. 141-184./ online : https://doi.org/10.2307/j.ctv11smnnj.13.

- Claire Deuticke/ Marie-Claire Gagnon/ Iris Oke/ Samira Plunger, Sammlungsbestände neu bewerten, in: Stefanie Kitzberger / Eva Klimpel (eds.), Sammeln, Aneignen, Übersetzen. Rosalia Rothansl, Mileva Stoisavljevic-Roller und die moderne Hausindustrie, New Tony Press, Berlin 2025, pp. 56.

- Manon Fougère/ Ljubica Jaksic/ Emilie Malmgren/ Viktoria Weber, „Volkskunst“ und „Hausindustrie“. Eine kurze (Begriffs-)Geschichte im Kontext von Kunstgewerbe und Museumspraxis um 1900, in: Stefanie Kitzenberg/ Eva Klimpel (eds.), Sammeln, Aneignen, Übersetzen. Rosalia Rothansl, Mileva Stoisavljevic-Roller und die moderne Hausindustrie, New Tony Press, Berlin 2025, pp. 27-29.

- See the catalogue: Christoph Thun-Hohenstein/ Anne-Kathrin Rossberg/ Elisabeth Schmuttermeier (eds.), Die Frauen der Wiener Werkstätte, Basel, Birkhäuser, 2020, p. 288.

Louisa Chaton is a Master’s candidate in the Dual Degree program at Sciences Po Paris and the École du Louvre, currently researching French-Austrian cultural exchanges through the work of Hilda Polsterer (1903–1969).